- Home

- Susan Stachler

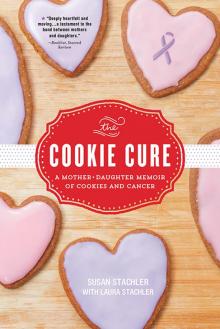

The Cookie Cure

The Cookie Cure Read online

Thank you for purchasing this eBook.

At Sourcebooks we believe one thing:

BOOKS CHANGE LIVES.

We would love to invite you to receive exclusive rewards. Sign up now for VIP savings, bonus content, early access to new ideas we're developing, and sneak peeks at our hottest titles!

Happy reading!

SIGN UP NOW!

Copyright © 2018 by Susan and Laura Stachler

Cover and internal design © 2018 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover design by Jennifer K. Beal Davis, jennykate.com

Cover image © Dmitry Zimin/Shutterstock

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems—except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews—without permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

This book is not intended as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified physician. The intent of this book is to provide accurate general information in regard to the subject matter covered. If medical advice or other expert help is needed, the services of an appropriate medical professional should be sought.

This book is a memoir. It reflects the author’s present recollections of experiences over a period of time. Some names and characteristics have been changed, some events have been compressed, and some dialogue has been re-created.

All brand names and product names used in this book are trademarks, registered trademarks, or trade names of their respective holders. Sourcebooks, Inc., is not associated with any product or vendor in this book.

Published by Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

sourcebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Stachler, Susan, author. | Stachler, Laura, author.

Title: The cookie cure : a mother/daughter memoir of cookies and cancer / Susan and Laura Stachler.

Description: Naperville, Illinois : Sourcebooks, [2018]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017030949 |

Subjects: LCSH: Stachler, Susan--Health. | Cancer--Patients--United States--Biography. | Businesswomen--United States--Biography. | Cookie industry--United States. | Mothers and daughters--United States.

Classification: LCC RC265.6.S73 A3 2018 | DDC 362.19699/40092 [B] --dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017030949

If ever there is tomorrow when we’re not together…there is something you must always remember. You are braver than you believe, stronger than you seem, and smarter than you think. But the most important thing is, even if we’re apart…I’ll always be with you.

—A. A. Milne

Contents

Front Cover

Title Page

Copyright

1. My Name Is Susan

2. Oh, To Be Tested

3. Going, Going, Gone

4. So That’s What It Feels Like

5. Aunt Sue, Meg Ryan, and Pretty Woman

6. Two Susans, One Day

7. Cancer Buddies

8. Dueling Patients

9. Nuke It!

10. The Driveway Commute

11. Double-Sided Tape

12. You Want Me To Do What?

13. This Little Cookie Went to Market

14. Two Hands on Deck

15. For Better or Worse, in Sickness and in Health

16. No Guts, No Glory

17. Open for Business

18. Caller ID

19. A Round of Margaritas

20. Sugar Crystals

21. Unsnappable

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

Back Cover

Dear Sue,

I didn’t know you were terminal until you were dead.

Mother and Dad raised us in a fun, loving home. You were my big sister, four years older than me, and we were inseparable. Our time together was filled with the normal things sisters do—shopping for clothes at Judy’s, learning how to play guitar, squeezing lemon juice on our hair to turn it blond, laying our freckled bodies out to try to get a sunny Southern California tan, watching Johnny Carson, and eating midnight snacks. And there was something else, something that somehow seemed normal at the time. You went to the doctor every three weeks.

How did I not know?

It all started one night when we went to Shakey’s Pizza with the rest of the family. We were all chatting, waiting for our pizza to arrive, when you said, “Daddy, I have something right here…” and rubbed your shoulder. And what did I think? Nothing. I was only ten. You were fourteen. But for some reason, I remember that moment very clearly. You went to see Dr. Swift, our pediatrician, and soon after, you went to the hospital for surgery. Mother and Dad bought a second TV and put it in my bedroom “for anyone in the family who happens to get sick.” The doctor told them you had Stage 4 Hodgkin’s disease—a blood cancer that affects lymph nodes—but they didn’t tell me about your diagnosis. They didn’t even tell you the full story.

Years after your death, they told me the doctors had given you three years to live and said you would not graduate from high school. I realize now how lucky we were—you lived eleven years longer than the doctors predicted you would. At the time, Mother and Dad simply told you that you had a blood disorder; they never said the word cancer. It was 1963, a different time. Now, everyone knows everything about everything. Instead of Webster’s Dictionary, we use Google. I carry a little device, about the size of a deck of cards, in my hand, and it can give me the answers to any question I have. Mother and Dad decided to protect you by not telling you everything. And you went to the doctor every three weeks for a checkup. It became a part of who you were, just something you did.

If Mother and Dad had told you that you only had three years to live, would you have been waiting to die? What if they had told you in the beginning, when you still felt well, that you had a limited amount of time left? You wouldn’t have been the same. Instead, we lived our lives, you went to the doctor every few weeks, and I didn’t even realize how sick you were. At least, not until you came to visit me during my freshman year of college.

I was so thrilled that everyone in the dorm would see me going out that night with my cool older sister. I was getting ready in my small, shared dorm room when the door flew open. You entered, gasping for air. Immediately, I turned to the rotary phone behind me and called the operator. “I have an emergency! My sister’s here, and she can’t breathe. She’s not breathing. I’m in the dorm on the third floor, USC campus.” You slid down from the edge of the bed onto the floor, slumped over. I rushed to you, shouting, “Sue, what’s wrong?” You couldn’t answer. You were still gasping, your head tilted back as you tried to suck in air. I went back to the phone and yelled into the receiver, “Please hurry! I need help!” I didn’t know what to do.

I ran into the hall, screaming, “Can someone help me?” It was early in the school year, and I didn’t know anyone on my floor yet. One, two, three doors down I found help. A girl hurriedly followed me back and helped me get you onto the bed. By then your mouth was clenched shut and your body was rigid. I didn’t know what was happening. Kneeling next to you on the bed, I sobbed as I wrapped my arms around you. I thought you were dying right there in my arms.

Finally, the paramedics arrived. As they got into position to help you, o

ne asked, “What happened here?”

All I knew to say was, “My sister has Hodgkin’s disease.”

Years later, after we both were married, I lived for our ridiculously long, twice-weekly phone calls. I was perplexed one Saturday when you couldn’t come to the phone. Hoxsie went to tell you I was calling but quickly got back on the line and said you wouldn’t be able to talk to me. He didn’t sound like himself.

A day later I got a call from Dad. “Laura, I’m calling from the hospital in Palm Springs. Your mother and I are here with Sue. You need to come as soon as you can. We are waiting with Hoxsie. Your sister is not doing well.”

Before I hung up the phone, I said, “You know I’ll be there as soon as I can. But, Dad, I can’t go in. I can’t see her this time.” I couldn’t bear the thought of you being sick again. My voice broke. “I can’t, Dad.”

You know Dad, calm and understanding. He just said, “Okay, honey, you just need to get here.”

When I arrived at the hospital, of course I went in to see you. I was terrified, but I walked into your hospital room. You were resting, your eyes closed.

“Sue.”

You blinked when I said your name and tried to look my way.

“Sue, it’s me. It’s Laura,” I said. “I’m right here. You’re doing such a good job. Everyone here is so nice, and they’re taking good care of you.” When I reached over the side rail of the bed and slid my hand into yours, I felt you squeeze my fingers. I blinked back tears, not wanting you to see how scared I was. “You’re doing such a good job. Please keep trying.”

I didn’t know if you had any strength left, but what if all you needed to help you get through this was for me to push you one more time? Did you hear me when I told you my plan? “Ken and I have already talked about it. When you go home, I’m coming to stay with you ’til you get better.”

Your calmness frightened me. You already knew, didn’t you? We would never see each other again.

When your hand released mine, Dad said, “Sue, you get some rest, sweetie. Why don’t you sleep a little?”

My heart started to race. You looked so tired but peaceful. I was shattered. I didn’t know what to think, wasn’t sure what was happening. All I knew was that you were very, very sick. As Dad stepped away from the side of your bed, he touched my arm, signaling it was time to go. I leaned over you. Could you hear me? “I know we never had to say this to each other,” I said, “but I love you.” I moved up to your forehead and kissed you. “I’m not leaving you,” I promised. “I’ll be right outside, and I’ll see you soon.”

I remember driving away from the hospital hours later, looking at the people in their cars going past. They didn’t even know what had just happened. You were gone.

1

My Name Is Susan

Isn’t it funny that from the time we’re born, we each respond to a name, our very own name? When you think about it, a name is just some letters and sounds put together, but it becomes our identity—who we are. It’s the first thing people learn about us (“Hi! My name is…”), and it’s stuck with us forever.

I got lucky. I like my name. I always have. Classic, simple: Susan. I’m named for my aunt Susan. I hear she was quite amazing, and I’ve always felt that being associated with her, purely through this five-letter name my parents bestowed upon me, makes me pretty special. That’s how it works, right? My aunt and me. Two girls, one name. We never met, but we have a bond that lasts forever.

Growing up, my ears would perk up at the slightest mention of Aunt Sue. I wanted to know more about this person: the other Susan, the original Susan. My aunt died before I was born, when she was twenty-eight. I came along four years later. It wasn’t like Mom went around talking about her sister all the time. But when she did, it was never so much what she said that drew me in, but how she said it. I grew to love Aunt Sue because Mom loved her, and I loved my mom. I took it upon myself to be the best Susan possible. I thought if Mom saw a glimmer of her sister in me, maybe, just maybe, she’d miss her a little bit less.

I constantly put pressure on myself to do things right. I took on having this name just like I do everything else—with full-on commitment—and the stress I sometimes feel about it is honestly a bit ridiculous. It’s not always easy being me. For some reason, even things that don’t matter in the big picture matter to me. Decisions as simple as whether to have M&M’S or Skittles for a movie snack or what appetizer to make for a family dinner have been known to put me in a quandary. I can’t help myself. I wish I could. But striving for my best works for me. So I’ve always wanted to get “being Susan” right.

I’m one of four kids. We’re boy, girl, boy, girl, and I’m number two. Mom says, “We all come with a thumbprint,” and mine has a definite pattern of control and organization. I plan, take charge, direct, sort out, and put things in order. I want things to be black and white. I like to know the end of the movie first, and I read the last page of a book before I begin chapter one. It might sound boring to some people, but I like to know what’s coming.

Ever since my first day of kindergarten, when I confidently announced to my class, “Hi! My name is Susan. I’m named for my aunt Sue,” I’ve liked school. Maybe it’s because I like structure and rules and following along. Go to class, take notes, take a test, then on to the next one. In elementary school, I was already setting goals for graduating high school and getting into a good college. The next thing I knew, I was twenty-two years old, a senior majoring in communication at Auburn University, and my school days were coming to an end. My diploma, my ticket to the outside world, would be in my hands in a matter of months.

Putting pressure on myself to do well in school was one thing, but I took it to a new level when I started off my senior year of college by buying a suit, walking it into my newly rented apartment, and hanging it in my closet. It was a traditional, jet-black, two-piece skirt suit with coordinating black leather heels. This would be my interview suit, and it would land me a job. I had no idea what kind of job I would get or even what I wanted to do, but I knew if the interview required me to wear a suit and heels, that would be a good start. Every day, as I pulled on jeans and a T-shirt, ready to zip off to class, I’d eye that suit. It was a constant reminder: stay focused.

In order to get a chance to wear that suit, I’d need a strong résumé. My experience as a server in a Mexican restaurant and a barbecue joint, with one summer of office-temp work mixed in, wasn’t going to be much help in the corporate world. As the weeks went by and I worried, What am I going to do to fill in the white space? I found myself working to keep my GPA up, piling on campus activities, and even volunteering for Relay For Life, a fund-raising event. Solid plan.

There was also something else going on in my life. One day after New Year’s, while I was still home on break, I heard the back door slam shut in the middle of the afternoon. My mom called out, “Ken, is that you? You okay?”

Dad answered with a resounding no. It was the first and only time I had ever heard my dad say he wasn’t okay. He had lost his job, and at the worst possible time. He’d been battling cancer and was still undergoing chemotherapy, and, meanwhile, Mom had been talking about taking action on one of her dreams: starting a bakery out of our house. I wished there was something I could do to help, but all I could do was go back to school, study hard, interview for jobs, and start a career. My parents gave me everything I ever needed—and a lot of what I wanted—and I couldn’t wait to call home and say, Mom and Dad, I have a job! Now there’s one less person for you to worry about.

As spring break approached, I looked forward to a week of hanging out at home and not really doing anything. Auburn University is in Alabama, a two-hour drive from our house in Atlanta. My friends were either going to the beach or on a cruise, but I was happy to head home. There had been a lot going on with my family, so I thought it would be nice to spend some time with them.

My boyfri

end, Randy, came home with me for a couple of days too. We had met at Auburn three years earlier and become best friends. He somehow managed to be the life of the party while at the same time keeping to himself, his nose in a book. He was born in Mississippi but had grown up in small towns in Louisiana, and he was a rugged guy with a baby face—totally intriguing. Luckily, my family loved him too, and he was always welcome at our house.

After dinner one night, as we were hanging out in the family room, Mom casually said to me, “Don’t forget you have a doctor’s appointment tomorrow.”

“What?” I shouldn’t have been surprised—Mom was always sneaking up on us with doctor’s appointments.

Mom said, “Yes, a checkup, and I got you in with the dentist on Wednesday.”

“The dentist too?” I was not pleased. I hated going to the doctor. The dentist was no better; actually, it was way worse. No matter how much I brushed and flossed, I still got cavities. I quickly gave my litany of reasons why I didn’t need to go to either appointment.

Mom just laughed. “Okay. Pick one.”

The next morning as I tried to leave for the doctor, I couldn’t keep my car from rolling down the steep angle of our driveway, and I got stuck. It was a stick shift, and I wasn’t good at driving it. Pressed for time, I had no choice but to get Randy so he could drive me. As I sat beside him in the waiting room, I felt self-conscious—it wasn’t exactly cool to drag your boyfriend along to your doctor’s appointment. Soon, the door opened and a nurse peered into the waiting room. “Susan?”

“Sorry about this,” I said to Randy. “I’ll be right back.”

I stepped on the scale, changed into the paper gown, and sat patiently as the nurse practitioner checked me over. I figured it was about time for her to be through, but she kept running her fingertips up and down, side to side, along my neck and over my collarbone. Again, up and down, side to side.

“Susan, have you ever felt anything here?” she asked.

The Cookie Cure

The Cookie Cure