- Home

- Susan Stachler

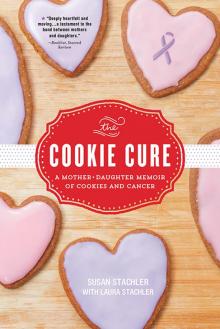

The Cookie Cure Page 8

The Cookie Cure Read online

Page 8

On my first day of radiation, I found myself happily greeting the receptionist. “Hi! We’re here—Susan Stachler.” I don’t know when I started doing this, but I heard myself say “we.” I didn’t want to be alone through any part of this, and I didn’t want Mom to feel left out either. We were in this together.

Mom became “my person.” She almost always knew what I was thinking, always stuck up for me, and was always tough and unwavering, even at moments when it must have been incredibly difficult. Being the caretaker is its own gig, and it’s not an easy task. There were plenty of times I was happier being me, rather than being in my mom’s shoes, even though I was the one with cancer.

This place was bright and fresh, with glass walls and an aquarium in the middle. But the atmosphere was glum. Mom and I were making small talk when a technician came to the waiting room. “Susan? We’re ready for you” she said, looking directly at Mom.

“I’m not Susan,” Mom responded, looking distressed. This had happened a few times.

“Mom, it’s okay.” I hopped out of my chair and gathered up my things. Mom was sensitive to the fact that she wasn’t the patient.

The technician showed me into a dark room with all kinds of equipment and a table in the middle. My therapy was going to be in the area of my neck, throat, and chest, so I had to lie faceup on the table, naked from the waist up, with my head placed in a doughnut-shaped pillow and my chin tilted back. There were two technicians, one on each side of me, and they adjusted me until my body lay exactly where they needed it. The technicians were doing specific calculations, and I was fascinated but uneasy, feeling like a turtle on its back—defenseless. This treatment was very precise, and every millimeter had to be accounted for.

The technicians took multiple imaging scans and measurements using a ruler of some sort, red laser beams, and bright lights. They were concentrating so hard on their jobs that there was no time for conversation or banter, and while I appreciated the attention they were paying to the process, I felt like Cancer Patient Number 146. It was like they temporarily forgot there was a person under the black marker they were using to outline exactly where the radiation should be targeted.

I stayed as still as possible, following the technicians’ instructions. But when they moved my head, my bandanna slipped, which upset me. No one had seen my head without my bandanna. I had barely even looked at it, but I knew that my hair had thinned considerably, and my head was bald in patches. I would wake up every morning, grab the bandanna, wrap it around my head, and secure it with a knot at the base of my neck before I even sat up. I desperately wanted to cry out, “Please, please, stop. I need to fix something.” And although this process—the scans and measurements—didn’t hurt physically, my self-esteem was bruised. This was a level of vulnerability I had never experienced before.

Just as I was about to speak up, one of the technicians, who was drawing the final line across my chin and who Mom and I would forever refer to as Marking Pen Lady, asked, “Are you the one who brought the orange chocolate chip cookies?”

Could this get more awkward? I thought. “Yes,” I answered. “My mom baked them.”

“Those were delicious.”

“My mom will be so happy to hear that you liked them.”

“I heard she runs a bakery,” the technician said. “Before you leave, I’d like to place an order. What else does your mom bake? Do you have a menu on you?”

Well, considering I was half-naked on a table, no. I didn’t have a brochure or menu on me, but I was ready to go tell Mom that she had a new customer.

Once they completed the process, I was scrambling to fix my bandanna and put my clothes back on when the technician motioned to my head and said, “You can go across the street to the women’s center, and they can do something for that.”

I suppose she was trying to be helpful, but her remark was so bold, and I already felt exposed. But I managed to remain composed and squeaked out, “Thank you. See you tomorrow. I’ll bring a menu with me.”

As I left, I decided that I’d get better at this. I promised myself that I would never feel this way again during my radiation. I’d get better at training myself to “escape,” to not feel vulnerable.

On the way to the car, I said, “Mom, guess what? There are a few people in the back who are interested in ordering from you. They want me to bring in a menu.”

The treatment process had been such an upsetting experience that I chose not to describe it to Mom. I couldn’t even tell her what the technician had said to me about my hair. By that point, if anyone had even looked at me wrong, Mom would have been livid. It would be years before I shared with her what had happened. For now, I spent the car ride home staring out the window, too mortified to say a word.

• • •

Have you ever seen the movie Groundhog Day? That’s what going to radiation came to feel like as I repeated the process over and over. Greet the receptionist and chat like I hadn’t just seen her the day before; sign in; wait in the lobby and stare at the pretty fish tank; go to the locker room to change my clothes; head into the large, dark, cold room with a mammoth machine that zapped me from above; then flip over so it could zap me from the back. The only thing that changed was my throat became more and more burned with each treatment. The zapping was painless, but afterward, it would start to hurt, a burning, unrelenting pain.

The only way I could get through it was to turn it into a game. I hated dropping my hospital gown and being naked on the cold table while the technicians positioned me. I found it funny that they wore protective aprons and left the room to stand shielded behind a thick glass wall while the machine blasted my bare skin.

Over the intercom, I heard, “Are you comfortable? Let us know if you need us.”

That made me laugh. Not wanting to move a muscle, I called out, “I’m good. Thank you.” The more time they’d spend making me “comfortable,” the more uncomfortable I would become. I’ll admit I had one constant worry, which seemed to be more pronounced when I was alone, trapped with my thoughts, staring at the machine above me: How does this work? And is it working on me? I learned to breathe and stay calm, and I trained my mind to escape. Sometimes I’d go to the beach, in my imagination, or to Old Town, San Diego, or to a Braves baseball game with Randy.

Once the radiation was over, no matter how I felt, I would return to the waiting room all smiles, desperate to hold it together for Mom.

At home, Mom was filling any orders she was able to get, but, in part because I was taking up so much of her time, she wasn’t drumming up a whole lot of business. She liked spending time in her bakery though, and she would work on tweaking recipes in the garage whenever she had a few minutes to spare. Sometimes this experimentation resulted in an abundance of baked goods in our house. That wasn’t a bad thing, except that swallowing had become a challenge for me. Mom liked having a reason to bake, so she would tell me about the people she had chatted with in the waiting room during my treatment that day and then ask, “If I bake some gingersnaps, will you bring them tomorrow?”

Soon we started bringing gingersnaps regularly to share with anyone who happened to be in the waiting room. It was great to see the reaction the cookies brought—people were smiling in a place where, frankly, there wasn’t much to smile about. I never said much, just handed out bags of cookies. It felt good to have something to do.

It was lucky my treatment coincided with the upcoming holidays, which garnered a few sales for Mom. It turned out that my Marking Pen Lady had placed a sizable order for a family party, buying all sorts of cakes and cookies. Mom was happy to sell anything, but her recipes were formulated for large quantities, so when she only sold one dozen cookies out of a batch of three dozen, that wasn’t ideal. Mom didn’t want to have to mess with figuring out how to divide an egg in half. When Marking Pen Lady ordered several different flavors, Mom had too many leftovers. I had taken a few business c

lasses and knew this was not a good return on her investment! But Mom enjoyed baking, and the stress relief it gave her was priceless, even if she was losing money as she tried to grow her business. Not wanting to appear like she was wheeling and dealing in the waiting room, she always brought extras for the patients, along with the paid deliveries she started bringing to the staff who were supporting her business.

Because we went to radiation treatments daily, we saw the same people in the waiting room all the time, and their reaction to my mom’s treats was consistently incredible. It was amazing how such a little thing could make such a big difference to people. I don’t know if it was the cookies themselves, the act of giving them away, or something else, but it definitely felt like something special was happening in that sad little waiting room.

Dr. Cline said my treatment would be finished the week of Thanksgiving, and Mom and I marked the date on the calendar, counting down the days. My throat hurt so badly I could barely eat, but I was hungry, and I could almost taste my favorite side dishes and Mom’s pecan pie, which would taste even sweeter knowing that my treatments were over. But with each treatment I had, the burning sensation in my throat got worse—so much so that Mom made an extra appointment for me with Dr. Cline. I was in bad shape.

Dr. Cline asked, “How bad is it, Susan?”

“It hurts some,” I answered.

Mom jumped in. “It doesn’t hurt some. Susan is in terrible pain. She can’t even get down the numbing medicine you prescribed.”

The radiation regimen I was on didn’t allow for breaks, but Dr. Cline decided it would be best to postpone my next treatment for a few days. The skin on my throat had become scaly on the outside, and whatever peach-fuzz hair I’d had left on the back of my head had burned off. I could barely speak, which was tricky when I wanted to chat with my friends at radiation or give cookies away, and it hurt to swallow even my own spit.

While I was trying my best to get through the last few treatments, Mom was putting extra effort into Thanksgiving. Who knew so many conversations could be had about candle colors and vegetable casseroles! She worked to put together a pretty table, delicious food, and homemade pies. My whole family gathered around the table, talking and eating, happy that we were all together and that I was nearly done with treatments. I took a couple bites of mashed potatoes, but I couldn’t swallow. I couldn’t believe it—of everything on the table, mashed potatoes were the easiest food to eat, and I couldn’t even get that down. I know it was irrational, but I was embarrassed my brothers and sister had to see me like that. What must they be thinking? I lowered my head, hoping no one would notice I was upset, and tried not to cry. This was supposed to be a celebration, and I felt like I was ruining it.

Suddenly, Mom got up and left the table. She returned with a little box and handed it to me. I opened it and found a pretty sterling-silver charm bracelet inscribed with my initials and a message: “Courage with a Smile. Love, Your Family.” I lost it. I had just been on the verge of crying over mashed potatoes… I didn’t deserve this gift.

“Thank you so much,” I said, barely able to get the words out. Everything—my frustration with the long treatment regimen, the pain I had been enduring, my fear and exhaustion—all came to a head at that moment. I started to cry.

Mom came around the table and gave me a gentle hug. “Let me help you put it on, Susan.” Her touch was the most soothing thing I had felt in days.

Dear Sue,

Memories of you carrying your green throat-spray bottle around the house came back to me as I drove to the pharmacy to buy the same stuff for Susan, hoping it would help ease her pain a little. It didn’t work for her, just like it didn’t work for you. You had excruciating pain, and while Susan did her best not to let on, I know she did too. I couldn’t fix it. It was devastating.

And while all this was going on, could I have been doing anything more ridiculous than baking cookies? Probably not. But I had bought a giant stainless steel mixer for my big kitchen in the garage, and the only thing I could do to distract Susan a little was bake. I’d insist that she bring cookies for the people I’d meet in the waiting room while she got zapped every day. So that’s what we did. I bought ingredients at the grocery store (I didn’t know how or where to buy wholesale) and baked dozens of cookies, and Susan gave them away. Her fellow patients liked them, and more importantly, they were distracted for a few minutes each day, and so was Susan. It wasn’t anything much, but it was nice, and it worked. It was one little thing I could do.

One particular day, there was a nice older gentleman in the radiation lobby, sitting in a wheelchair, his wife next to him. Susan and I sat down near them and began chatting. I asked the gentleman how he was getting along. The couple described the side effects of his therapy—fatigue and terrible weakness. Although visibly disheartened, they were trying to stay optimistic. He was very sick. They wanted to know which of us was there for treatment, and, of course, it surprised them that Susan, my young, beautiful daughter, was the one who was sick.

A few minutes later, the nurse called Susan back. As she walked away, Susan turned to us, smiled, and gave me that look of hers—the one that said, It’s all right, Mom. Don’t worry.

I waved and said, “I’ll be right here,” just as I did every day. As Susan disappeared down the hall and around the corner, I looked at the older couple and shrugged.

The gentleman commented, “She’s just so young, but at least she seems to be doing very well with her cancer.” Then he added, “I hope one day, when I am not in pain, I can smile like your daughter.”

I sighed. “She is in pain. Terrible pain… But she smiles anyway.”

The sweeter she was, the more it hurt me.

10

The Driveway Commute

Treatment was over, and I was behind in life. At least, I was behind in what I believed that I, as a college graduate, should be doing. I felt an urgency to figure out what I was going to do next, but even though my treatment was over, I still didn’t feel or look like myself. It was maddening. I had expected to start feeling well again right away, but what I didn’t realize was I would not bounce back that quickly. No one, not Dr. Weens or Dr. Cline or any of the nurses we met along the way, had warned me about this. Recovery would be a gradual process—and let’s just say patience isn’t my forte. I had a bunch of checkup appointments and follow-up scans lined up, but I wanted to fill my days with something productive. Luckily, Mom had anticipated that I’d find this unstructured time frustrating.

One day when I was tired of hanging around the house, she casually asked, “When you feel like it, do you want to come out to the shop?” She was trying to make me feel useful, and it worked. I felt so much better knowing that, even if I couldn’t go out and get a job yet, I could at least help Mom a little with her business. I could let myself off the hook. Going to her bakery felt like getting out of the house, but I could always sit down if I felt tired or go back inside and lie down on the couch. With just a few weeks until Christmas (my favorite holiday), I decided not to stress or overthink things too much. I’d allow myself to enjoy December and then reevaluate in January.

With the holidays upon us, Mom received a fair number of dessert orders. Baked goods and the holidays just seem to go hand in hand. People needed sweets for their family get-togethers, office celebrations, cocktail parties, and cookie swaps. I’d never heard of a cookie swap before, but customers would ask Mom, “Do you mind leaving the label off the box? I don’t want my friends to know I didn’t bake them!” She would oblige, but then they’d taste one and say, “I don’t know why I had you do that. No one is going to believe I baked these cookies. They’re too good!”

People came to Mom’s shop enthusiastic and ready to buy the perfect desserts to complete their holiday experience. She had struggled to solicit orders before, but now the hustle and bustle of the holiday season and people coming in and out made the shop lively and

fun to be around. Word of mouth had spread, and she had a steady flow of customers. I got in the habit of going to the shop in the morning, when few customers came, because I was reluctant to be seen by strangers or have to answer their questions. And, really, I didn’t want Mom to have to do that either. People had a way of putting her on the spot, asking her about me as if I weren’t standing right there.

I wasn’t able to help Mom much in the shop, but it gave me somewhere to go, and I liked that. Mom said I made her nervous, just standing there watching her, and she’d push me to sit down and get comfortable. I’d sit cross-legged on top of the front counter, which was a steel baking table with a solid butcher-block top. It was a family heirloom from Carver’s, the pie-and-burger restaurant that her parents had owned in LA. I would sit there, chat with Mom, and sometimes put labels on boxes. It was neat seeing the labels in print, hundreds of them on a roll, since I had created the design.

When Mom was first starting her business, she called me at school and said, “So I was thinking… I need a logo for my bakery. What about one of your drawings?”

Pleased but surprised, I asked, “You want one of my little sketches? Are you sure?”

“You don’t have to if you don’t want to,” Mom said, “but I’d love that.”

I didn’t see myself as an artist, although I spent hours drawing what my high school art teacher had deemed “flat, dull stick figures,” but I sketched out a logo for Mom. It was kind of incredible now to see my work applied to hundreds of boxes of my mom’s baked goods.

Although I avoided the shop during the day when it was busy, it was exciting to look out the window and see people pulling up the driveway to pick up cakes, cookies by the dozen, and tins of gingersnaps. Somehow, even in the midst of caring for Dad and me when we were sick, Mom had found the time and energy to make one of her own dreams come true. I was prouder of her than I could say.

The Cookie Cure

The Cookie Cure